America is a young country. We forget this sometimes, especially those of us who are riding the strange, aimless ship that is this star-spangled nation. We don't have castles (not real ones) and we don't have anything but trees that are properly ancient. Nothing we do here has been going on for more than a few centuries, which is pocket change time for the rest of the world, especially on the other side of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Our attempts at culture and refinement must look quaint to those who can casually walk the streets and hills of regions that have already seen a handful of empires come and go, that have been growing produce and flowers since before America was a glimmer in the tea-stained teeth of a British colonist. All told, we've been making wine in the United States for all of 70 years, give or take, and our soil is just now starting to yield the right levels of nutrients to produce respectable stuff. For a very long time the wine that came out of the much-revered (and let's face it, overrated) Napa Valley of California was considered cut-rate swill. It's what people bought for formal events they didn't care about, what the misers of the family brought to the reunion. Guys like the Gallo Brothers made a small fortune on the cheap stuff, but before long some proper wine crafters started working on barrels of palatable potables. These days, California, Oregon and Washington make some damn decent wine, but this has led to a certain degree of snobbery about the stuff. I think we Americans need to adjust our perceptions.

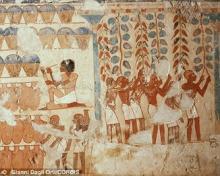

Wine is old. It's one of the oldest cultured products of our adventurous species. The earliest evidence we have of wine production dates back to around 8000 BCE around the Black Sea region, which remains a robust wine-producing locale, as well as for cognac. Let us consider what 8000 BCE looked like. This is an era before the majority of recorded history, when the concept of cities was novel and written law was a futuristic innovation. Plainly, people have been drinking wine since we were three hairs short of chimpanzees.

That's why it's so baffling that wine has become a thing of elitism as of late. Sure, there have always been preferred vintages that go for more money than the simple stuff the commoners drink, but this has become especially pronounced in the past few decades. Somehow, especially in America, the divide between rich and poor was drawn in two, long dribbles of pricey Pinot Noir and Carlo Rossi. High-end wine and "the cheap stuff" have been put in two dramatically different categories, resulting in a downright classist perspective on what people drink. This is absurd because the majority of affordable wines (in the 5-12 dollar range) are perfectly acceptable compared to the ultra-cheap poison that gets sold in boxes and jugs.

Really, wine ought to reclaim its place as the universal drink of revelry after a few interminable American decades as a signifier of wealth. This really is a problem for the culture of the United States, too. Europeans and those few Asian countries that haven't ignored or forbidden wine understand that there's a spectrum in viticulture, as with all things. There's table wine, the stuff you drink with your sandwich at lunch. It's not complex and you don't have to let it swim around on your palate so you can pick out the notes of lavender and sea air, or whatever the hell wine snobs look for in their fermented grape juice. Wine is the food/drug we consume as a reminder that we're alive, and most of life takes place in the mundane, not the spectacular.

So, it's my recommendation that Americans learn to drink wine as if it's the ancient, universal libation it truly is. There's nothing wrong with marveling at the complexity of a symphonic Bordeaux or lingering in the sharp power of a Carneros vintage, but there's also no reason to dismiss the simple pleasure of a cheap, local bottle at dinner on a Wednesday.